This article is part of U.S. Democracy Day, a nationwide collaborative on Sept. 15, the International Day of Democracy, in which news organizations cover how democracy works and the threats it faces. To learn more, visit usdemocracyday.org.

(NATIONAL) As of 2022, 1.2 million Native Americans were unregistered to vote across the United States. With the country’s second largest Native population living in Oklahoma, the state also had the lowest voter turnout in the general election in 2020.

Ginny Underwood, the Director of Oklahoma-based Rock the Native Vote told NBC News, “We’ve been invisible but we’re deeply affected by the things that are happening around us. We know how important it is to have a voice and to be able to have a say in policy.”

Decisions made by elected officials have significant impacts on Native Americans and tribal nations. Many actions by past presidents are still felt by Native people today, particularly in the state of Oklahoma. As part of VNN Oklahoma’s Democracy Day Coverage, we are diving into some of the decisions that have had the biggest influence in life in Indian Country and beyond.

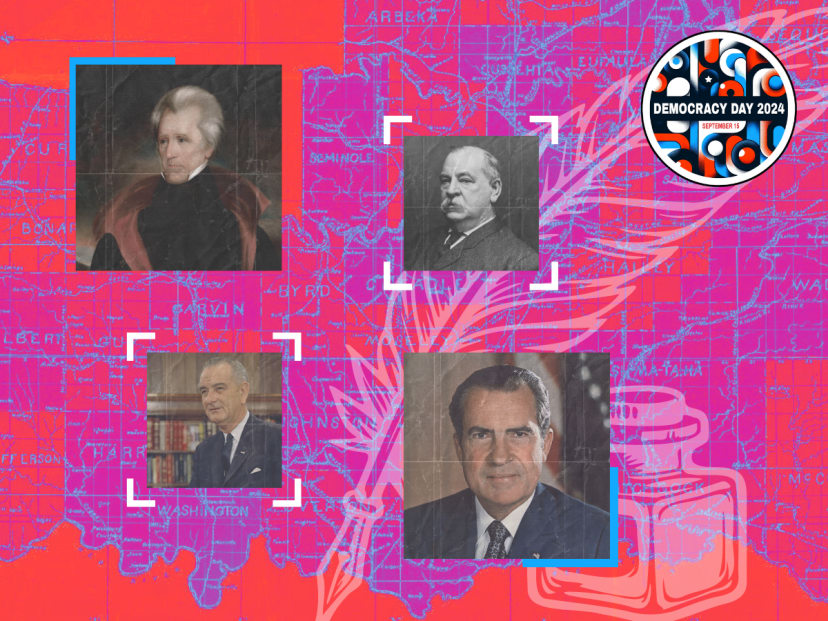

President Andrew Jackson

One of the most consequential presidents to American Indian policy was Andrew Jackson. In 1830, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which authorized the forced removal of tribes living east of the Mississippi River west to Indian Country. Jackson said he believed the removal of the Five Civilized Tribes would allow the southeastern United States to become more wealthy and powerful.

Jackson told Congress it gave him pleasure to announce, “that the benevolent policy of the Government, steadily pursued for nearly thirty years, in relation to the removal of the Indians beyond the white settlements is approaching to a happy consummation.”

The forced removal, known by many as “The Trail of Tears”, was a murderous journey for the Native Americans. According to the National Park Service, it’s estimated that 3,500 Muscogee Creek citizens died in Alabama as they were forced west. The aftermath of the forced removal and all that followed is still felt today through intergenerational trauma in Native communities.

President Grover Cleveland

President Grover Cleveland’s signing of the Dawes Act on February 8, 1887 also negatively impacted Indigenous Oklahomans for generations. After the Trail of Tears, the Dawes Act forced tribal members to assimilate by dividing their new land into allotments, effectively destroying the communal way of life that tribes had been accustomed to for centuries.

To receive an allotment, Native Americans had to enroll on the Dawes Rolls. This allotment system also paved the way for legalized theft of Native American land and mineral rights, which intensified after oil was discovered in Oklahoma.

President William McKinley

The signing of The Curtis Act in 1898 by President William McKinley continued the pattern of harmful policy for Native Americans. This new act effectively abolished tribal government, permitting the federal government to determine who was and was not a tribal citizen.

After the act’s passage, tribal governments needed congressional approval for any laws they wanted to pass. The Curtis Act was the beginning of full congressional control in Indian Territory.

President Theodore Roosevelt

Despite the obstacles they faced, leaders from The so-called Five Civilized Tribes (Muscogee, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole) entered the 20th century still fighting to exercise their sovereignty. In 1905, leaders from each of the tribes held a convention to draw up a constitution for the “State of Sequoyah.”

However, President Theodore Roosevelt rejected the proposal. Oklahoma became a state in 1907. While the state’s constitution pledged to never question the federal government’s jurisdiction over Native Americans, its immediate actions to remove protections for Native Americans proved otherwise.

Over a decade later, Indian Country policy began to slightly improve.

President Calvin Coolidge

Up until the 20th century, many Native Americans were not actual citizens of the United States. They were instead considered “domestic foreigners”. The big push for citizenship came following World War I, in which many Native Americans served in the U.S. military despite not being citizens.

On June 2, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act, which allowed for all Native Americans to become U.S. citizens.

Brian Hosmer, History Department Head at Oklahoma State University, told VNN about two thirds of Indigenous People were already citizens when this act was signed. And it didn’t automatically mean they would be able to vote. In fact, many states took steps to prevent the Native vote.

“The most popular way to prevent Indian people from exercising their franchise was through the stipulation that’s in the Constitution, and it says Indians Not Taxed,” said Hosmer. “So this was a clever, you might say nefarious way of turning sovereignty against Indigenous people so the argument was well you can’t vote in these elections because your Guardianship or the Trust status falls under this Indians Not Taxed.”

Indigenous people still face barriers to voting in the U.S., especially those who live in rural areas far from polling locations. From 2015 to 2020, the Native American Voting Rights Coalition (NAVRC) found that factors that discouraged Native political participation included geographical isolation, physical and natural barriers, poorly maintained or non-existent roads, distance and limited hours of government offices, technological barriers and the digital divide, low levels of educational attainment, depressed socio-economic conditions, homelessness and housing insecurity, non-traditional mailing addresses such as post office boxes, lack of funding for elections, and discrimination against Native Americans.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt

The 1930’s marked another change in Indian Country policy.

In 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Indian Reorganization Act. With this act, the allotment of tribal lands came to an end. Tribal governments were also incentivized to create constitutions similar to the U.S. constitution, which was ironically inspired in part by the Iroquois Confederacy of Nations concepts.

Funds for Indian Education were set aside and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) began hiring more people to work in the agency.

However, it’s important to note that critics of this act felt that it failed to recognize that tribal nations varied greatly, and many governing systems were different from the federal government’s.

President Lyndon B. Johnson

President Lyndon Johnson continued efforts to strengthen the Native Vote by signing the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

A portion of the act stated: “No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State or political subdivision to deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.”

In a special message to Congress on March 6, 1968, Johnson discussed the need to advocate for self-determination for Native Americans, saying the U.S. must work towards a standard of living for Native people that would be equal to non-Native people.

“The greatest hope for Indian progress lies in the emergence of Indian leadership and initiative in solving Indian problems,” Johnson said at the time. “Indians must have a voice in making the plans and decisions in programs which are important to their daily life.”

President Richard Nixon

For centuries, one of the greatest injustices to tribal nations and Native people in the US has been loss of land. Experts estimate that number stands at 99 percent of their historical landbase.

President Richard Nixon recognized this and sought to correct it by returning some of it. The return of Blue Lake in New Mexico to the Taos Pueblo Community marked the first significant return of land (55,000 acres) to Native people in 200 years.

Upon signing the bill, Nixon said, “This is a bill that represents justice, because in 1906 an injustice was done in which land involved in this bill…was taken from the Taos Pueblos Indians. And now, after all those years, the Congress of the United States returns the land to whom it belongs.”

And it wasn’t the only landback move Nixon made.

He signed an executive order returning Mount Adams to the Yakima Tribe. And he also signed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, the largest land claims settlement in U.S. history.

Though, the Alaska deal proved to be a very complex one, as the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act created Native profit-making corporations that received 45.5 million acres of land and $1 billion, as opposed to designating reservations. Thus, land was not truly given back in that case, and instead owned by shareholders of the Native corporations.

While Nixon is widely remembered for Watergate and being forced to resign, many Native community members still consider him one of their greatest advocates. His Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, which allowed tribal governments to exercise their full sovereignty, was signed into law by President Gerald R. Ford in 1975.

Past, Present, and Future

Decisions made by U.S. presidents over the last two hundred years still impact Native American Communities today.

During this time, Native American health has been consistently poorer compared with other Americans. This includes lower life expectancy, higher likelihood of disease, and higher rate of abuse, neglect, and assault.

Healthy People 2030 is a Department of Health and Human Services project that sets data-driven national objectives to improve health and well-being in the United States over the next decade. Civic Participation is listed as a social determinant of health under the Healthy People 2030 “Social and Community Context” domain, one of five domains identified in the project.

“Participating in the electoral process by voting or registering others to vote is an example of civic participation that impacts health,” researchers found. “A study of 44 countries (including the United States) found that voter participation was associated with better self-reported health, even after controlling for individual and country characteristics. In another study, individuals who did not vote reported poorer health in subsequent years.”

Coming up next in VNN Oklahoma’s Native perspective election coverage, we will focus on the impacts recent presidential administrations have had on Indian Country.

VNN’s Native District counters misinformation and disinformation by providing accurate and reflective Native American coverage as well as resources and events. Our work also helps to preserve Native American culture for future generations. But we can’t do it alone. Click here to support our Native District today.